Week 2: Gifts, commodities, and spheres of exchange

or, The reality of society and the bourgeois individual

Ryan Schram

ANTH 1002: Anthropology for a better world

ryan.schram@sydney.edu.au

Social Sciences Building 410

August 12, 2025

Main reading: West (2012)

Other reading: Eriksen (2015); Lyon (2020)

Lecture outline available at: https://anthrograph.rschram.org/1002/2025/02

Are you new here?

Welcome to the class. If you have just joined ANTH 1002:

Log on to Canvas today, read the preliminary materials for the class, and my recent announcements to the class.

Read the instructions for the assignments, including the general instructions for weekly writing assignments and the information about the Week 3 “early feedback” out-of-class quiz.

Say hello to your fellow students on the Discussions page.

Set your weekly routine for the semester now. Sticking with a weekly cycle is the most important way to make sure you learn in this class.

Tutorials start on Wednesday. If you have not been allocated to a tutorial but you are certain you will take this class this semester, please contact Ryan today.

From an egocentric to a sociocentric perspective

To be able to understand Tuvalu, you have to make a big switch in your perspective

- It’s not migration, it’s relocation.

- It’s not individuals leaving one society and entering another, it’s a society moving.

We can make a similar change in thinking to understand why the world is weird

- Society is not just a bunch of individuals living next to each other, even though that is what seems natural and obvious

- When making decisions in everyday life, it feels like each of us is

simply doing what we choose is best for us. We each act as individual,

rational maximizers of utility.

- That’s the duck. What’s the rabbit?

Learning to see the social, collective dimension of existence instead of individuals is anthropology’s way of challenging very influential ideas about how the contemporary world works, and what it can be.

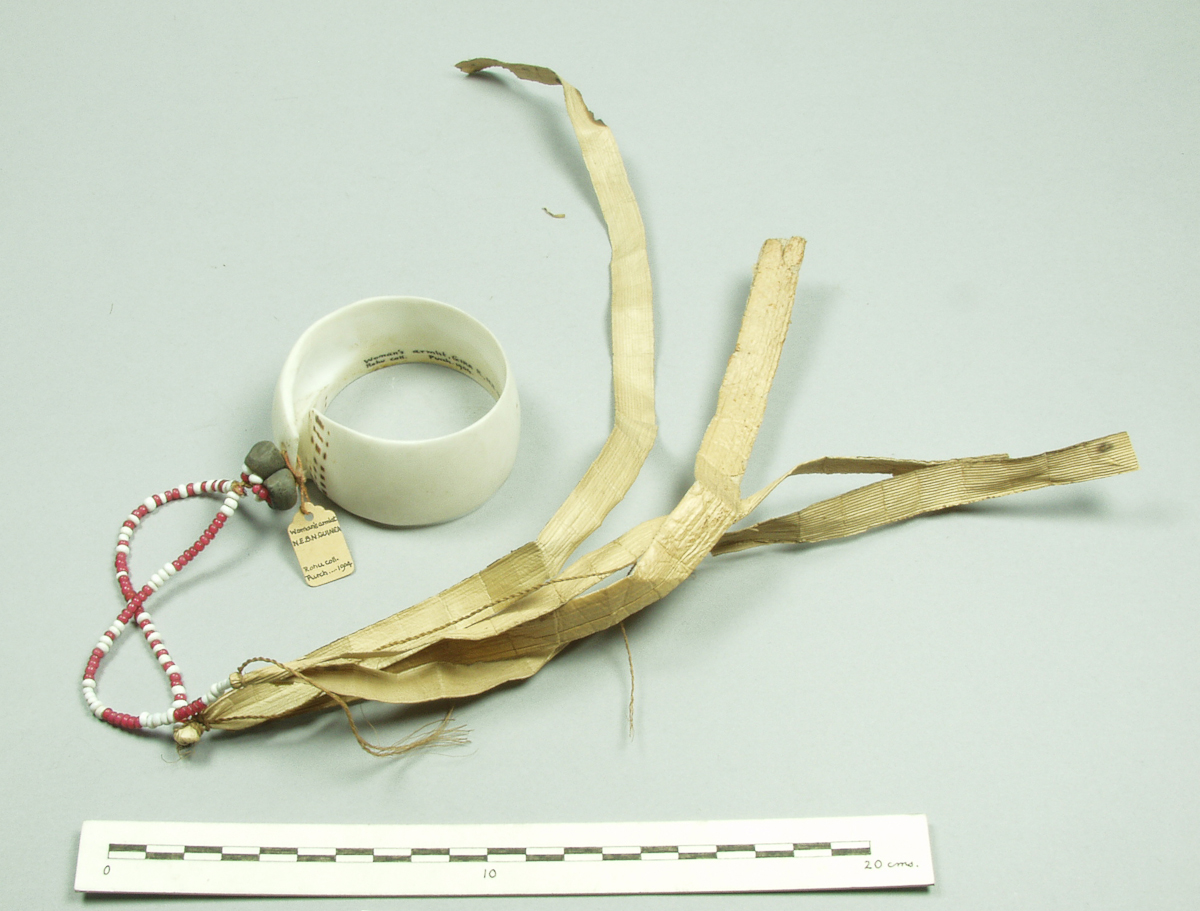

An “arm ornament”

A “necklace”

![An ornate, handcrafted necklace is suspended against a neutral grey background. The necklace is made of long strands of small, flat, disc-shaped beads in varying shades of pink and red ochre. It hangs from two points, creating a draped loop. The strand on the left hangs straight down. The strand on the right is shorter and features a tassel-like pendant. This pendant consists of a thicker, beaded section leading down to a light-colored, cone-shaped element. Dangling from the base of the cone are several shorter strings of the same reddish beads, each ending with a larger, translucent, shell-like pendant [gen AI description]. Chief’s necklace of red shell discs with pendants of pearl shell, black plant seeds (banana?) and palm fibre. The red shell discs are interspersed with white beads and four long cylindrical black beads. The pendant is made from a circular piece of shell with holes around the edge. From each hole hands a length of red beads topped with a seed. the shell discs are threaded parallel to each other. A piece of pearl shell and palm fibre hangs at the bottom of each sting. 1872. Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, 1890.5.1. https://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/collections-online#/item/prm-object-63161.](/media/bagi.jpg)

Coins and bills

![A close-up shot of several pairs of hands around a patterned tablecloth, counting and stacking piles of paper money [gen AI description]. Men counting bills and coins at a table in Wadaheya, an Auhelawa village on Normanby Island, Papua New Guinea, in 2006.](/media/money.jpg)

Yams

![Numerous long, woven baskets filled with yams sit on a gravel ground at in an island village near the beach, with people gathered in the background [gen AI description]. A collection of baskets of yams (Dioscorea alata) brought to an event in Tupwagidu, an Auhelawa village on Normanby Island, Papua New Guinea in 2004.](/media/yams.jpg)

Durkheim and Mauss

Emile Durkheim is a founding figure of sociology and anthropology

- He wanted to analyze society as an objective fact

- Society is a collective consciousness, like the Borg, from Star Trek (yes).

Marcel Mauss was a nephew and student of Durkheim

- Applied a Durkheimian analysis to economic activity

- Reciprocity is an obligation underlying many if not all transactions

Mauss’s argument clashes with his own culture’s conventional understanding of economic activity

Mauss grew up in a world in which everyone assumed that people acted as self-interested rational maximizers

For Adam Smith, for instance, says

- “[There is] a certain propensity in human nature …: the propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another” (Smith [1776] 1843, 6)

And yet, most people in most places don’t do this. Exchanges take the form of presents. Often people exchange identical things.

Gifts create obligations

Mauss says: Because you have to.

Gifts come with obligations because a gift is part of the system of total services. Specifically, giving a gift involves a triple obligation:

- The obligation to give

- The obligation to receive

- The obligation to reciprocate, or to give back to one who has given.

Society, in essence, is a total system. Reciprocity is an expression of this fundamental reality of society. We may not even be aware of this state of interdependence, but it is still there.

Gifts have spirit

For Mauss, the Maori word hau means the “spirit of the thing given” (Mauss [1925] 1990, 10).

When someone gives a gift, they give part of themselves.

“The hau wishes to return to its birthplace” (Mauss [1925] 1990, 12).

Total services

What, then, is society?

Mauss says that the essence of society is a “system of total services” (Mauss [1925] 1990, 5–6)

In a system of total services,

- everything one does is for someone else, and

- other people do everything for you.

It is a state of total interdependence.

Yam gardening in Auhelawa

Auhelawa is a society of people living on the south coast of Duau (Normanby Island), off the eastern tip of Papua New Guinea.

Every family in Auhelawa produces most of their own food grown on their own lands, and the most important of these are

- ʻwateya (Dioscorea alata)

- halutu (Dioscorea esculenta)

Yet although most of people’s effort and thinking goes into growing these yams, most of the ʻwateya are not grown as food for one’s family.

The best halutu are also preserved.

Tiv spheres of exchange

What if everything you owned “wished to return to its birthplace” (Mauss [1925] 1990, 12)?

Everything of value would be embedded in social relationships.

In many societies the embeddedness of value takes the form of a system that organizes objects into distinct, ranked spheres of exchange. One example is the Tiv of Nigeria, who have three spheres:

- Women as wives

- Prestige items: brass rods, tugudu cloth, slaves

- Subsistence items: food, utensils, chickens, tools

Some things, like land, cannot be exchanged for anything, but are inherited (Bohannan 1955).

Money in Tiv society: Bohannan’s prediction

Bohannan claimed that money would disrupt the separation of spheres of exchange. However…

- Money was initially placed in the lowest of spheres, or even outside of the three spheres (Bohannan 1955, 68). It continued to mainly be exchanged against low-ranking items (Parry and Bloch 1989, 13–14).

- Other scholars have noted that money does not have this revolutionizing effect on similar systems (Hoskins 1997, 186–88).

We got apples

![A close-up shot of a large pile of fresh red apples filling the entire frame, with small produce stickers visible on a few of them [gen AI description]. Apples on display at a supermarket in downtown Sydney, 2022](/media/apples.jpg)

What pairs well with apples?

Go to this Mentimeter poll: https://www.menti.com/alp1jpwhtwx7 (or go to https://menti.com and use code

3888 5750).

Select which one of the objects we’ve seen so far has the most in common with apples

Think of the value-relationship that normally defines these things.

- Shell valuables

- ʻWateya (Dioscorea alata yams)

- Kina and toea (currency in Papua New Guinea)

- Tugudu cloth

- Chickens

Talk with each other. Why did you choose what you chose?

Commodities and capitalism

- Commodities are bought and sold for a price.

- You can think of commodities as a “sphere of exchange.” When you exchange commodities for money, and back again, you are following certain rules.

- The sale of commodities generates a profit.

- A system of producing, selling and distributing commodities as the main form of economic system is associated with capitalism.

Private property creates a new kind of society

For capitalism to emerge, first the concept that one’s property can be owned privately has to be instituted.

- Private property gives me the right to exclude other people from my property, like a fence.

Talk about selling out…

A worker under capitalism brings “his own hide to market and has nothing to expect but – a hiding” (Marx [1867] 1972, 343).

What do you think he means by this? Buzz about this. What do you associate with the word Capitalism? Marxism? When did you first hear these words? Have you ever read the Communist Manifesto?

Capitalism is…

- Capitalism is a system in which the means of production (capital, or productive wealth) are privately owned by one social class, the bourgeois class.

- Capitalism is a system in which nobody else has access to the means of production; in order to live, people have to sell their labor.

Either gifts or commodities?

This might sound like a simple dichotomy:

societies based on gifts, reciprocity, and a system of total services;

capitalist societies based on commodity production and consumption.

Instead, consider this possibility:

Every society is based on a system of total services, even if its members don’t know it and cannot see it.

Some societies impose a specific set of social fictions:

- valuable things can be private property, and

- your body and your labor power is your private property, and you can sell it if you have to.

We see both the reality of society and the fiction of individual alienation in every society, and they interact in several different ways.

A side note: There is a paradox in our concept of society

Bourgeois culture teaches us that we are each individual economic actors and that there is no society on which we depend.

But societies are real. We really are all part of a system of total services.

Yet, also, every society is based on a fiction.

We need to be part of a social order

But any one social order will involve lying to ourselves.

- And some social fictions completely obscure the existence of any social ties.